- Afghanistan

- Africa

- Budget Management

- Defense

- Economy

- Education

- Energy

- Environment

- Global Diplomacy

- Health Care

- Homeland Security

- Immigration

- International Trade

- Iraq

- Judicial Nominations

- Middle East

- National Security

- Veterans

|

Home >

News & Policies >

December 2004

|

For Immediate Release

Office of the Press Secretary

December 16, 2004

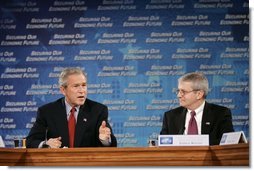

President Discusses Budget, Tax Relief at White House Conference

Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center

Washington, D.C.

9:32 A.M. EST

THE PRESIDENT: Thank you all. (Applause.) Thank you all for coming. Last night I had the honor of attending a reception for those who have participated in these series of panels, and I had a chance to thank them. I said something I think is true, which is, citizens can actually effect policy in Washington. In other words, I think people who end up writing laws listen to the voices of the people who -- and can be affected by citizen participation. So I want to thank you all for doing this.

We're talking about significant issues over the course of these

couple of days. We'll talk about an important issue today, which is,

how do we keep the economy growing; how do we deal with deficits. And

I want to thank you all for sharing your wisdom about how to do so.

We're talking about significant issues over the course of these

couple of days. We'll talk about an important issue today, which is,

how do we keep the economy growing; how do we deal with deficits. And

I want to thank you all for sharing your wisdom about how to do so.

One thing is for certain: In all we do, we've got to make sure the economy grows. One of the reasons why we have a deficit is because the economy stopped growing. And as you can tell from the previous four years, I strongly believe that the role of government is to create an environment that encourages capital flows and job creation through wise fiscal policy. And as a result of the tax relief we passed, the economy is growing. And one of the things that I know we need to do is to make sure there's certainty in the tax code -- not only simplification of the tax code, but certainty in the tax code. So I'll be talking to Congress about -- that we need to make sure there is permanency in the tax relief we passed, so people can plan.

If the deficit is an issue -- which it is -- therefore, it's going to require some tough choices on the spending side. In other words, the strategy is going to be to grow the economy through reasonable tax policy, but to make sure the deficit is dealt with by being wise about how we spend money. That's where Josh comes in -- he's the -- as the Director of the OMB, he gets to help us decide where the tough choices will be made. I look forward to working with Congress on fiscal restraint. And it's not going to be easy. It turns out appropriators take their titles seriously. (Laughter.)

Our job is to work with them, which we will, to bring some fiscal restraint -- continue to bring fiscal restraint -- after all, non-defense discretionary spending -- non-defense, non-homeland discretionary spending has declined from 15 percent in 2001 to less than 1 percent in the appropriations bill I just signed, which is good progress. What I'm saying is we're going to submit a tough budget, and I look forward to working with Congress on the tough budget.

Secondly, I fully recognize, and this administration recognizes, there -- we have a deficit when it comes to entitlement programs, unfunded liabilities. And I want to thank the experts, and the folks here, who understand that. The first issue is to explain to Congress and the American people the size of the problem -- and I suspect Congressman Penny will do that, as well as Dr. Roper -- and the problems in both Social Security and Medicare.

The issues of baby boomers like us retiring, relative to the number

of payers into the system, should say to Congress and the American

people, "We have a problem." And the fundamental question that faces

government, are we willing to confront the problem now or pass it on to

future Congresses and future generations. I made a declaration to the

American people that now is the time to confront Social Security. And

so I am looking forward to working with members of both chambers and

both parties to confront this issue today before it becomes more

acute.

The issues of baby boomers like us retiring, relative to the number

of payers into the system, should say to Congress and the American

people, "We have a problem." And the fundamental question that faces

government, are we willing to confront the problem now or pass it on to

future Congresses and future generations. I made a declaration to the

American people that now is the time to confront Social Security. And

so I am looking forward to working with members of both chambers and

both parties to confront this issue today before it becomes more

acute.

And by doing so, we will send a message not only to the American people that we're here for the right reason, but we'll send a message to the financial markets that we recognize we have an issue with both short-term deficits and the long-term deficits of unfunded liabilities to the entitlement programs.

And I want to thank the panelists here for helping to create awareness, which is the first step toward solving a problem. The first step in Washington if you're interested in helping is to convince people that there is a problem that needs to be addressed. And once we have achieved that objective, then there will be an interesting dialogue about how to solve the problem.

I've got some principles that I've laid out. And, first, on Social Security, it's very important for seniors to understand nothing will change. In other words, nobody is going to take away your check. You'll receive that which has been promised. Secondly, I do not believe we ought to be raising payroll taxes to achieve the objective of a sound Social Security system. Thirdly, I believe younger workers ought to be able to take some of their own payroll taxes and set them up in a personal savings account, which will earn a better rate of return, encourage ownership and savings, and provide a new way of -- let me just say, reforming -- modernizing the system to reflect what many workers are already experiencing in America, the capacity to manage your own asset base that government cannot take away.

So with those principles in mind, I'm open-minded -- (laughter) --

with the members of Congress. (Laughter and applause.)

So with those principles in mind, I'm open-minded -- (laughter) --

with the members of Congress. (Laughter and applause.)

Anyway, thank you all for coming. I'm looking forward to the discussion.

DIRECTOR BOLTEN: Mr. President, thank you. Thank you for convening us. It warms my budget heart -- (laughter) -- that you've taken the time to come and talk about fiscal responsibility, which is so important, especially at this time. We've come through some tough years, Mr. President, during your tenure.

As you entered office the economy was entering recession, we had the attacks of 9/11, we've had the war on terror, we've had corporate scandals that undermined confidence in the business community. All of those, together, took a great toll on our economy, and especially on our budget situation, as you mentioned. And we've started to turn it around. The economy is well out of recession, it's growing strongly, as I think our panelists will talk about. And as a result of that we are seeing a dramatically improving budget situation.

We originally projected our 2004 deficit to be about 4.5 percent of GDP, and when we got the final numbers just a few weeks ago, it was down to 3.6 percent of GDP, a dramatic improvement. Now, that's still too large, but it's headed in the right direction. You mentioned, Mr. President, the 2005 spending bills that you just signed last week. I think those have to be regarded as a fiscal success, because you called on the Congress almost a year ago to pass those spending bills with growth of less than 4 percent overall, and especially to keep the non-national security related portion of that spending below 1 percent, and they delivered. And that's the bill that you signed just last week. We're working now, Mr. President, as you know, on the 2006 budget. And I'm hopeful that we will keep that momentum of spending restraint going.

What I think we will be able to show when we present your budget, about six or seven weeks from now, is that we are ahead of pace to meet your goal of cutting the deficit in half over the next five years. And I think that's very important. And I think our panelists will talk a little bit about why that is.

So let's step back a little bit from the Budget Director's preoccupations and talk more broadly about the economy. Our first panelist is Jim Glassman, who is senior U.S. economist at JP Morgan Chase. He's a frequent commentator in the financial press; I think well-known in the financial community.

And Jim, let me open it with you and ask you to talk about how the

budget situation is related to the economy overall, because that's

really what people care about.

And Jim, let me open it with you and ask you to talk about how the

budget situation is related to the economy overall, because that's

really what people care about.

MR. GLASSMAN: All right. Thanks, Josh. Thanks, President Bush, for inviting us here to participate in this discussion. It's a privilege.

The federal budget is tied very closely to the fortunes of the economy. When the economy is down, revenues are down. When the economy comes back, revenues come back. In the last several years, we've seen that link very closely. The economy slowed down, revenues dried up, the budget deficit widened. It's happened many times before. And in Wall Street, Wall Street understands this link between the economy and the budget, and that's why -- we anticipate that these circumstances are going to be temporary, and that's why long-term interest rates today are at the lowest level in our lifetime, even though we have a budget deficit that's widened.

And in fact, now, with the economy on the mend, the revenues are coming back, and the budget deficit appears to us to be turning the corner. So I think the prospects are looking quite good for the budgets going into in the next several years.

Now to me, the link between the economy and the budget tells you there's an important message here, and that is: Policies that enhance our growth potential are just as important for our long-run fiscal health as are policies to reform Social Security and health care reform. We know how to do this, because over the last several decades, we've been reforming our economy -- deregulating many businesses, breaking down the barriers to trade. And it's no surprise that countries all around the world are embracing free market principles. Free markets is the formula that has built the U.S. economy to be the economic powerhouse that it is.

Now, I realize the last several years have been challenging for a lot of folks, and it's hard for folks to step back and appreciate the amazing things that are going on in the U.S. economy when they're struggling with this, with the current circumstances. But I have to tell you, what we are watching around the U.S. economy is quite extraordinary, and I would like to highlight two things in particular that are important features of what's going on in the U.S. economy, because it tells us -- that basic message is it tells us that we're on the right paths, and number two, it tells us how we might build on the policies that are helping to encourage growth.

The first important observation: productivity. Productivity in the U.S. economy is growing almost three times as fast as the experts anticipated several years ago, a decade ago. Now, we know why that's happening: Economic reform has strength competition; the competition has unleashed innovation; that innovation is driving down the cost of technology; and businesses are investing in tools that allow us to do our jobs more efficiently. Why that's important? Because most of us believe that what's driving this productivity is information technology.

Now, in my mind when we're at an extraordinary moment like this with rapid changes in technology, it opens up a lot of frontiers. Who is it that brings that technology and creates growth? Who is that drives the economy? It's small businesses. That's where the dynamic heart of the economy is. And so policies that focus on making the business environment user-friendly for small businesses, like the tax reform, are an important element of building on this productivity performance that's going on, and building on the information technology.

Second important aspect of what's going on in the U.S. economy -- everybody knows we faced an incredible number of shocks in the last several years. These shocks, which, by the way, destroyed almost half of the stock's market value in a short period of time, for a moment, were potentially as devastating as the shocks that triggered the Great Depression. And yet, the experts tell us the recession we just suffered in the last several years was the mildest recession in modern times. That tells you something about the resilience of the U.S. economy. It tells you that we have a very flexible economy to absorb these kinds of shocks. And I personally think that this is the result of a lot of the reforms that we've been putting in place in the last several decades. It has made us much more resilient.

I find this an even more incredible event because when you think about it, we had very little help around the world. The U.S. economy was carrying most of the load during this time. Japan, the number two economy, was trapped by deflation. Many of our new partners in East Asia have linked the U.S. economy, and they're depending on their linkage with the U.S. economy to bring -- in hopes of a better future. The European region has been very slow growing. They've been consumed by their own problems. So, frankly, we've been in a very delicate place in the last several years; the U.S. economy was the main engine that was driving this. And yet, we had this incredible performance. I think it's quite important.

Now, when you ask economists to think about the future, where we're likely to go, it's very natural -- the natural tendency is to believe that we're going to be slowing down eventually -- and we can give you all kinds of reasons why this is going to happen -- demographics, productivity slows down. My guess is we would have told you this story 10 years ago, 20 years ago, 100 years ago.

And I think what's quite incredible -- I'm, frankly, somewhat skeptical of this vision that we all have, because, if you think about it, we've been growing 3.5 percent to 4 percent per year since the Civil War. If we can match that performance in the next 50 years -- and I don't see why that's so hard to do, given the kinds of things we are discovering about our economy and the kinds of benefits we see from all this reform -- then I think the fiscal challenge that we see in our mind's eye will be a lot less daunting than is commonly understood.

So, of course, I don't want to say that growth can solve all our problems. It won't. There clearly are challenges on the fiscal side, and it's important that we strengthen the link between personal effort and reward. And that's why it's right this forum should be focusing on Social Security reform and health care reform. Thank you.

THE PRESIDENT: May I say something?

DIRECTOR BOLTEN: Mr. President. (Laughter.)

THE PRESIDENT: Thank you. (Laughter.) Who says my Cabinet does everything I tell them to? (Laughter.)

You know, it's interesting, you talked about the Great Depression, and if I might toot our horn a little bit, one of my predecessors raised taxes and implemented protectionist policies in the face of an economic downturn, and as a result, there was 10 years of depression. We chose a different path, given a recession. We cut taxes and worked to open up markets. And as you said, the recession was one of the shallowest.

And the reason I bring that up is that wise fiscal policy is vital in order to keep confidence in our markets and economic vitality growing. And that's one of the subjects we'll be talking to Congress about, which is wise fiscal policy. And that is the direct connection between the budget and spending and confidence by people who are willing to risk capital, and therefore provide monies necessary to grow our job base.

DIRECTOR BOLTEN: Mr. President, let's talk a little bit about how investors see those issues that you and Jim Glassman have just been talking about. Liz Ann Sonders is chief investment strategist to Charles Schwab and Company. She's a regular contributor to TV and print media on the market issues that investors care about.

And Liz Ann, let me just open it to you and ask you, how do investors see those broad macroeconomic issues that Jim was just talking about?

MS. SONDERS: Thanks, Josh. Thanks, Mr. President. I do spend a lot of time out on the road talking to individual investors. And I will say that the deficit issue is probably, if not the number one, certainly in the top three questions I get. I think there is a terrific amount of misunderstanding, though, about the nature of deficits, how you get there, how do you get out of a deficit situation, the cause and effect aspects of it, and I'll talk about that in a moment.

And we know that higher deficits are a burden on future taxpayers, but I think what, in particular, the market would like to see is the process by which we go about fixing this problem. And I think the markets are less concerned about the number itself and don't have some grand vision of an immediate surplus, but the process by which we solve that problem.

There's a lot of ways to do that. It is all about choice. And certainly, there's one theory, that the only way to solve it is to raise taxes. I don't happen to be in that camp, and I would absolutely agree with Jim and certainly with this administration that the policies absolutely have to be pro-growth.

And I think the other benefit that we have right now, and Marty Feldstein talked about this yesterday, the difference between the Waco Summit and this conference today as representing a very strong economy right now versus a couple of years ago. And what that allows you to do is have this much stronger platform from which you can make a sometimes tougher decision. And I think that's a very important set of circumstances right now. I would agree with Jim, also, at the bond markets perception of this, the fact that long-term interest rates are low so we have at least have that camp of investors telling you that maybe the risks aren't quite high as some of the pessimists might suggest.

Forecasting is also difficult. I know your Administration suggested that going beyond five years is a tough task. And it is. The market, however, builds itself on making forecasts for the future, and often times will develop a consensus about something, and I will say that I think the consensus is one maybe of a little bit -- maybe not pessimism, but not a lot of optimism from a budget deficit perspective. So, I think the opportunity comes with showing some effort. And you can really turn the psychology of the market very, very quickly under a circumstance where maybe market participants are actually pleasantly surprised by the turn of events.

Typically, when you look back in history, and you look at processes by which we've improved a deficit situation, those that have been accompanied by better economic growth have typically been those where the focus has been on spending restraint, entitlement reform. Those times where we have improved the deficit, but it's been in conjunction with weaker economic growth are typically those periods where tax increases have been the process by which we have gotten there.

And I also think that many investors misunderstand the relationship between deficits and interest rates, and there is a theory building now that higher deficits automatically mean higher interest rates. Well, case in point, it's just the most recent experience, but we can even go back to the late '90s -- the reason why we went from deficit to surplus was because the economy was so strong. Because the economy was strong, the Federal Reserve was raising interest rates, the reason why we went into deficit was because the economy got weak, which is the reason why the Federal Reserve had to lower interest rates. So you have to understand, again, the cause and effect here.

The path of least resistance, of course, is to make everybody happy. But something has to give. You've all talked about this, the "no free lunch" idea. But I'm just a strong believer that entitlement reform and long-term priorities take precedent right now over short-term fixes, certainly if it required tax increases. And I think that, Mr. President, you talked about having political capital, I'll go back to this idea that we now have economic capital that allows us to not disregard the short-term fixes for the deficit here, but really take this opportunity for long-term structural reform.

I'm a big believer in personal accounts, empowering investors. My firm built by "the Man," Chuck Schwab, is all about empowering individual investors. And I think these long-term adjustments that need to be made, which is really a part of this whole conference, are so important right now. And I think that's absolutely what the market wants to see.

Thanks.

THE PRESIDENT: Good job. You're not suggesting that economic forecasts are as reliable as exit polling, are you? (Laughter.)

MS. SONDERS: I'm not going there. (Laughter.)

DIRECTOR BOLTEN: Mr. President, I'm going to move on. (Laughter.) I'm glad that Liz Ann raised the distinction, as you did in your opening remarks between our short-term picture and our long-term picture. Our short-term picture is, indeed, looking a lot better. I think we'll be able to show a very clear path toward your goal of cutting the deficit in half over the next five years. But the long-term picture is very challenging. We're very honored to have with us Tim Penny, who is a professor and co-director of the Hubert Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs. He's also a former Democratic Congressman and an expert on a lot of the long-term issues we're talking about.

And, Congressman, let me turn it over to you and ask you to talk a little bit about what are these entitlement programs, and why are they important for our long-term budget picture?

CONGRESSMAN PENNY: Well, I think -- thanks, Josh, and Mr. President. I think the first thing to note is that the long-term picture is rather bleak, that the status quo is unsustainable. And when you talk about the difference between discretionary and entitlement spending, that tells the story.

Discretionary spending, as you referenced earlier, is the part of the budget that we control annually. It comes out of the general fund; it's education, it's agriculture, it's defense, it's a whole lot of stuff that we think about as the government.

But the entitlement programs are those that are on automatic pilot. They're spelled out in law and the checks go out year in and year out, based on the definitions in law. So if you're a veteran, you're entitled to certain health care benefits under this system. If you're a farmer and you grow certain crops, you're entitled to subsidies. There are some that are means-tested. In terms, we give them to you only if you need them; and that's where our welfare programs and much of our Medicaid spending comes into play. And then there are the non-means tested entitlement programs, and among those are Medicare for the senior citizens and Social Security for senior citizens. So, they're age-based programs.

And those entitlement programs are the biggest chunk of the federal budget. I think it's constructive to look back over history. In 1964, all of these entitlement programs, plus interest on the debt, which is also a payment we can't avoid, consumed about 33 percent of the federal budget. By 1984, shortly after I arrived in Congress, they consumed 57 percent of the federal budget, and today they consume 61 percent of the federal budget.

Now, let's look forward a few decades and see where we're going to be with entitlement spending. By the year 2040, just three -- well, actually four of these sort of mandatory programs are going to eat up every dime -- income taxes, payroll taxes, all other revenues that we collect for the federal government: Medicaid, Medicare, Social Security and interest on the debt will eat up everything. There won't be a dollar left in the budget for anything else by the year 2040. That tells you the long-term picture, and it is bleak. So something has to give. Doing nothing is not an option.

Let's look at Social Security alone. And this is something that my colleague, Mr. Parsons, will speak to in a few minutes. There are huge unfunded liabilities here. We haven't honestly saved the current Social Security trust fund. Even though extra payroll tax dollars are coming in each year, they're not honestly being set aside for this program. Just by the year 2040, there's about $5 trillion of unfunded liability in that program. Now, we've got to come up with the money somehow to replace those promised dollars. And it's no easy task. And I know that a million, a billion, a trillion sort of gets lost on the average listener, so I always like to explain that if you're looking at a trillion dollars, just imagine spending a dollar every second, and it would take you 32,000 years to spend a trillion dollars. So even in Washington, that's big money. (Laughter.) Or as we say in farm country, it's not chicken feed. (Laughter.)

So the other way you can look at this is your Social Security statement comes in the mail every year, and it gives you some sense of your promised benefits in the Social Security system. But on page two of this statement, there's an interesting asterisk. And the asterisk says, "By about the year 2040, we're not going to be able to pay you all of the benefits that we're promising you. We're going to be about 25 percent short of what we need to pay those benefits." So, what does that mean we would have to do if we wait until the last minute to fix this program? We'd either have to cut benefits dramatically, or we'd have to impose the equivalent of a 50-percent payroll tax increase on workers to get the money into the system to honor the promised benefits.

So huge benefits cuts or a huge tax increase -- I don't think that's where we want to go, especially since 80 percent of Americans now pay more in payroll taxes than income taxes. I don't think that's a solution that they're going to applaud. But, frankly, it is the kind of solution we're left with if we wait too long to fix the mess. We waited too long 20 years ago. When I first arrived in Congress in 1983, we had a Social Security shortfall. We were borrowing money out of the Medicare fund to pay monthly Social Security checks. So what did we do, because we were already in a crisis? We cut benefits by delaying cost-of-living adjustments; we cut benefits by raising the retirement age, first to 67 and -- 66, and ultimately to 67; and we increased payroll taxes, significantly, during the 1980s. And so we basically said to future workers, based on that legislation in 1983